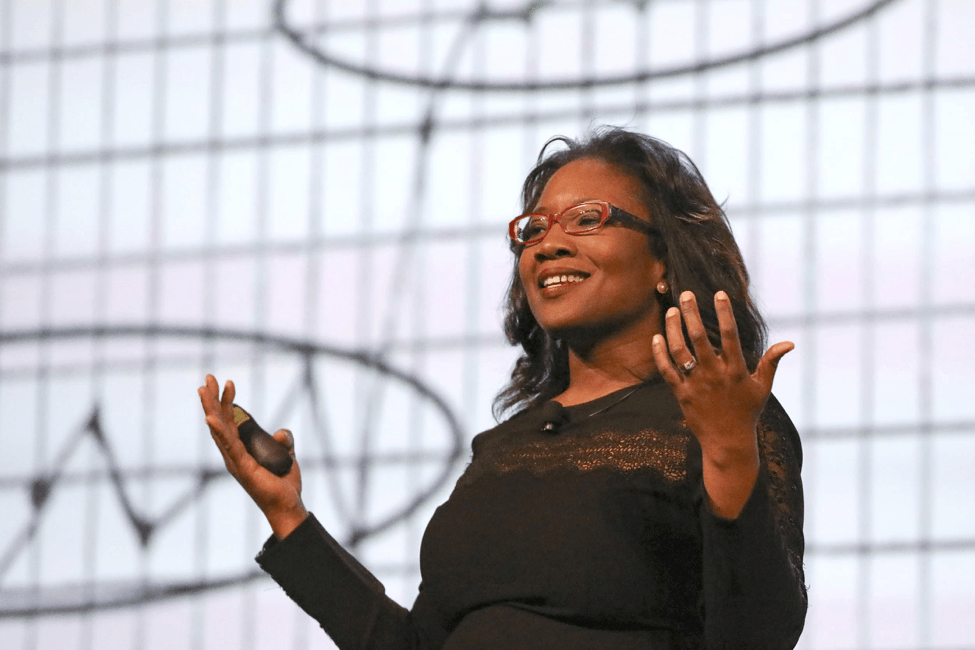

Talithia Williams: Breaking down barriers

Women are often the unsung heroes in history. Women’s History Month is our chance to pay homage to these heroic women, and celebrate the accomplishments of today’s heroes, who are making incredible contributions in every profession. This month is also an opportunity to grapple as a community with some of the challenges and shortcomings in our society that hold women back.

To help kick start the conversation, I caught up with Talithia Williams, whom I met during the 2017 Tableau Conference. Talithia is a professor, author, speaker, and TV host. Talithia has a deep passion for statistics and data, and has made significant contributions to these fields in her many diverse pursuits. She is someone that I personally look up to as a black woman in tech and so it was my absolute pleasure to tackle these topics with her.

Maraki: During your TC18 presentation, you shared that you’d recently written a book called, Power in Numbers: The Rebel Women in Mathematics. What motivated you to write this book?

Talithia: I grew up unaware of black women’s contribution to STEM and the impact it has had on society. As a little girl I enjoyed and felt stimulated by the challenge and rigor of math and science, but I never saw people, both black and woman like me, who did it, so I didn’t think it was attainable. My brothers dreamed of playing basketball, and they had the images on TV to see it. Even though they never made it to the NBA, they never doubted it was something they could have achieved if they worked hard at it. Power in Numbers is a way to leave something behind, similar to bread crumbs in fairy tales, for young women of all races to see themselves as scientists, mathematicians, data scientists, and statisticians. The book is something I would have wanted to see as a young girl. Once you know that there was a first who came before you, you can imagine yourself being next.

Maraki: As you wrote your book, were there any themes that you found among many of the women?

Talithia: Many of the women often faced open and outright prejudice, especially the first women to enroll in all-male math departments. There were women who couldn’t attend classes because they weren’t allowed to be in classes with male students and this was common. There were women who were disowned by their families or had to sneak around to explore their mathematical interests because their family couldn’t understand why they wanted to pursue a male-dominated field. Women were pushing to do the stuff that they were passionate about and worked so hard to overcome obstacles that were put in their way. Even after women were “allowed” into graduate programs or do research, in certain instances, their credit was taken by the lead male scientist. So, the beauty in the story is that they struggled, had people who didn’t believe in them, but they still have stories of how they persevered and that’s the beauty of their stories.

Maraki: It sounds like some of these women in your book ran into the glass ceiling. What are some examples of what we can do to break even more barriers now?

Talithia: For many of these women, the ceiling wasn’t as clear as glass! It wasn’t something they could even see through to the other side! In order to help more women to break the glass ceiling, everyone has to be conscious of the biases we have when making decisions and make a point to invite everyone to the table. For example, since I’m a professor, when hiring new professors, we tend to want to bring people in who are similar to us. Perhaps they went to the same graduate school or their research area is similar to ours. It is natural to gravitate to candidates who look like you. You have to be intentional to think about how other people could also contribute to your organization. When looking at applications, you have to make sure you aren’t being biased based on privilege. How do you compare two people who are equally intelligent, but maybe one hasn’t had as much access? You have to be conscious. You have to acknowledge your bias and make sure you are not feeding it and using it to make those decisions.

Maraki: You mentioned not being biased based on privilege or access. Based on your experience, what are the differences in the experiences of women in STEM who hail from different socioeconomic backgrounds?

Talithia: The field could be more thoughtful of what it means to come in at different levels of wealth and what it means to be a mother in this field. If you’re a single mom needing to travel to a conference, how are these conferences handling childcare? Because the field has primarily been for men, they didn’t have to think about whether men were bringing kids. Conferences are being more intentional on how they can be more thoughtful for both mothers and fathers by, for example, having lactation rooms or babysitters on site. These are the types of small things that could hinder women from fully participating in a particular field.

Maraki: One of the things you mentioned is having to go the extra mile to prove credibility or a sense of belonging. What is the tax on the individual who has to do this?

Talithia: There is both a mental and emotional tax. It takes mental energy to get pass having to engage and be thoughtful about how to engage. Often in these spaces there are so few people who look like you, you feel as though you have to represent all women or your whole race. I always feel like I have to be conscious of the fact that there were so many other people I was representing, because what I say reflects all women or black people. You think four times about what you say because you can’t take it back for your race or gender and that adds mental and physical stress. If we didn’t have to go through that process, we could make so many more contributions to society. The more thought I have to put into what I’m going to say and how I’m going to say it, then the less I’m listening or paying attention because I’m worried about how I’m being perceived. If you take that away, then I have 100% of myself to give to the moment. I could bring all of myself. It frees us to be more creative and more confident and not feeling like saying something incorrectly would be a poor representation of a whole people.

Maraki: Can you tell me your thoughts on the role mentorship and representation plays in getting women into and keeping them in STEM?

Talithia: It’s HUGE. And I don’t think you have to be mentored by someone who looks like you. You can have great mentorship by someone who is different from you, but is invested in you. And not just mentorship, but also sponsorship, how do you put someone’s name forward when an opportunity comes up. I don’t think anyone has gotten to their current position without having a mentor or sponsor who have taken notice of their talent and abilities. It is important to find someone you can sit down and talk to about your five-year plan, and maybe it isn’t your direct supervisor if your plan includes taking her job! For me, mentorship made all the difference. I had to reach out to my mentors when I was ready to quit graduate school or was ready to give up. When they would tell me they had the same feeling of wanting to quit, it gave me the perseverance to stick it out.

And in terms of representation, part of the reason I do the Sacred Sistahs Conference is to show young women that there are women who look like them that are doing amazing, cool things in math, science, engineering, and computer science. For me, having the images of Sylvia Bozeman and my NASA mentor Claudia Alexander, who looked like me and had done what I'm doing stuck in my mind. I think it is key for this next generation to see themselves as scientists and scholars in the media as well. It is one of the reasons I got excited to host the show NOVA Wonders on PBS. They wanted to inspire the next generation of scientists.

Maraki: At the end of your TC18 presentation you mentioned a quote by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “There is power in unity and there is power in numbers.” Why is this quote important to you?

Talithia: Because of where we are as a society, it feels like we’ve become disunified. People are operating in silos. When we do that, we lose some of our power. There is power in large groups of us coming together for a unified vision. How can we find causes that unify us and find the power in numbers to come around that vision and that unity? In some ways, the book is meant to do that. Here are these women who were individuals, but there is power in the unity of them coming together saying, “We want a part of this STEM pie. We want to be considered equal. We want the same access to rich, complex mathematics and statistics and science that men have.” And as more women obtained that, we see it as a possibility because all of these women have come before me and done it.

It's inspiring to talk to women like Talithia, who are challenging norms and are powerful, female role models in traditionally male-dominated professions. My hope is that we can one day define a new normal - a world in which seeing women (and other underrepresented folks) thrive and break new ground in STEM is an expected and celebrated part of our everyday. Maybe we won’t even need a Women’s History Month...after all, there isn’t a Men's History Month the last time I checked.