Why the data on homelessness and COVID-19 is a call to action for leaders

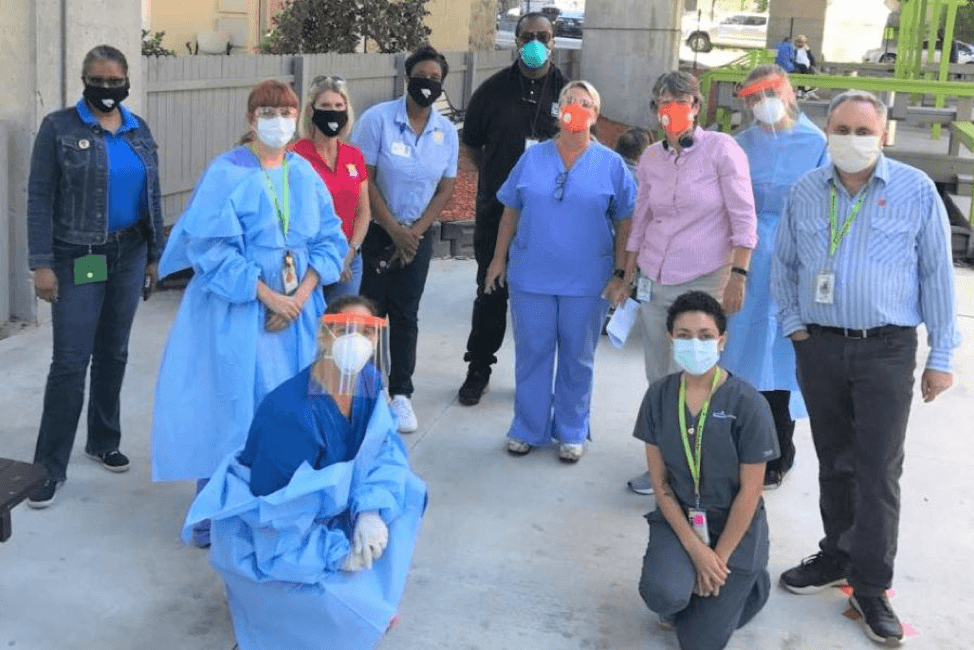

Investing in data infrastructure enabled Jacksonville, Florida to swiftly roll out COVID-19 testing for homeless individuals in May (courtesy of Sulzbacher)

In early July 2020, Tableau Foundation and Community Solutions just announced a $2 million commitment to expand and scale the data capacity of the 81 communities working to bring about a functional end to homelessness. This new grant signals the vital importance of continuing to invest in solutions to homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic and the uncertain economic times ahead. To learn more about the grant, read our previous blog post.

Before COVID-19, the biggest challenge facing many communities across the U.S.—including Tableau’s home of Seattle—was homelessness. The number of people experiencing homelessness on a given night has risen for the past several years, due to a range of factors from housing unaffordability to poverty. But just as cities and smaller communities alike were making real progress against the challenge and helping people into housing, the pandemic hit.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 has forced policymakers to focus their efforts on stopping the spread of the virus. Efforts to stop the spread of the virus have underscored that ending homelessness is a public health imperative. States and cities have worked with urgency to move people off the streets and into safety, recognizing they are at high risk of infection, complication, and transmission. While efforts are now ramping up to make sure that unhoused individuals are protected amid the outbreak, COVID-19 is, as one expert has said: “an enormous crisis superimposed on an existing crisis.”

As the public health and economic threats of the pandemic persist, it’s imperative that communities and policymakers not lose sight of the needs of their homeless neighbors. In conversations with our homeless services partner organizations, we’ve learned how COVID-19 is complicating the response to homeless, and why it’s so critical that leaders continue to prioritize this effort. We’ve also been reminded of the crucial role that data can play in understanding the needs of the homeless population amid the pandemic, and as communities work to stabilize going forward. Nothing about this situation is easy, but our partners are confident that focused effort and real-time data can help ensure that communities can help people out of homelessness and into health. Here are some of the key takeaways that we’ve heard from our partners.

COVID-19 is exacerbating the existing challenges of homelessness

In many cities, homelessness was already a visible crisis. “But in some respects, COVID-19 has exposed something that's very hard to see in normal times, which is the lack of accountability often at a community level for vulnerable people—that’s all now out in the open,” Rosanne Haggerty, President and CEO of our partner organization Community Solutions, tells me.

What that means is that the existing homeless services infrastructure in many places, from shelters to nonprofit organizations to local agencies, have needed to radically change their operations to respond to COVID-19, and are struggling under the pressure. Communal kitchens can’t be sustained during an infectious disease pandemic, so more people are going hungry or relying on different resources for food. To comply with social distancing, shelters have had to significantly reduce their capacity, or shut down entirely. Providers have worked quickly to respond to these challenges in several places by connecting unhoused people with units in vacant hotels and motels, where they can safely quarantine.

Even with reduced capacity, though, the risks posed by congregated settings like homeless shelters have become clear. Many shelters have struggled to access personal protective equipment for frontline staff and the people they serve. A report from the CDC describes the situation in a shelter in King County, Washington: “Residents were able to leave the shelters if they returned by curfew. Sleeping mats in each of the shelters were spaced ≤3 feet apart. Shelter C did not have alcohol-based hand sanitizer or on-site showers; residents used shelter shuttles or public transportation to access public showers. Staff members intermittently wore cloth face coverings or face masks; however, these were not provided to residents.”

The pandemic, says Joy Moses, Director of the Homelessness Research Institute at our partner organization the National Alliance to End Homelessness, is also highlighting the pre-existing health challenges that so many homeless people face. NAEH just published their 2020 report, and in it they describe research that found that people experiencing homelessness have physical conditions that mirror those of people 15-20 years older than them. Another study found that 84% of unsheltered homeless people self-report physical health conditions.

These pre-existing vulnerabilities, on top of the inability of large parts of the homeless services infrastructure to operate during a pandemic, is leaving homeless populations especially vulnerable. We’re already seeing the effects: Outbreaks have been spreading rapidly in homeless shelters across the country, among both residents and staff.

Homelessness and public health: A need for data

Homeless service providers and public health agencies are working rapidly to contain these outbreaks and address the escalating needs of the homeless population amid the pandemic. “At the CDC, we’re doing qualitative data collection to understand what the barriers are to hygiene like hand washing for people experiencing homeless so that can help inform our guidance,” says Emily Mosites, senior advisor on health and homelessness at the CDC. The CDC is also going to be collecting information on the universal testing events that are being conducted at homeless shelters across the country to better understand the outbreaks and how they spread.

For advocates like Mosites, that’s a step in the right direction. “There hasn’t been much uniformity in what information the homeless services system was collecting on people who were symptomatic or who tested positive, because it wasn’t required,” she says. “Without that complete and up-to-date information, we’re always going to be one step behind on what we need to be doing.” That’s a problem for people within the homeless population, and for communities more broadly, Mosites adds: “Anytime there’s uncontrolled infectious disease spread in a group of people, no matter who they are, that’s a threat to everyone,” she says. All of our partners in the homeless services space are adamant that homeless be considered not only as a social issue, but as a public health issue—with the data reporting and analysis to fuel understanding and inform solutions.

We have data-driven solutions that work

“We have an urgent problem on our hands that is affecting our most vulnerable populations and making whole communities vulnerable, but guess what? We have a tested remedy for this,” Haggerty says. “We don’t have to wring our hands. But we do have to get to work right away.”

COVID-19 has added a layer of urgency onto an already urgent situation. And it threatens to exacerbate it further. Community Solutions consulted with the Columbia University economist Brendan O’Flaherty, who estimates that the homeless population may increase by up to 45% due to the virus and the associated economic fallout.

But the solution is still the same: Understanding the scope of the situation in every community, and focusing on getting people connected with stable housing.

This is the approach that Community Solutions has been taking for years with Built for Zero—a national network of more than 80 communities across the country working to measurably reduce and end homelessness. At the core of the Built for Zero approach is a “by-name” list—a real-time dataset that contains every person in a community experiencing homelessness, and what their needs are to exit homelessness. By understanding the dynamics of homelessness in their community, cities and counties have created coordinated, data-driven systems that can drive down the number of people experiencing homelessness. Amid COVID-19, Haggerty tells me, those communities that have already invested in the data-for-homelessness approach are more able to be responsive to the crisis.

In Jacksonville, Florida, and Phoenix, Arizona, the close coordination among homeless service providers forged through their investment in Built for Zero has enabled the rollout of extensive testing at shelters and efforts to house people in hotels. “And there's this rock-solid commitment to these most vulnerable folks that they've gotten into hotel rooms that no one's going back to homelessness,” Haggerty says. “All of the communities I’ve spoken to say that they are going to find a way to move everyone from there to housing.”

“We’re seeing the communities, even in the face of no clear plan around anything having to do with a public health disaster like this, just doing what needed to be done—organizing, using data,” Haggerty adds. “Communities that had a by-name list had a tool, essentially a live public health registry, they could use to triage and get a head start on who needed to be assisted in what way.”

Both from a social and individual well-being perspective, and a public health perspective, COVID-19 is showing, as Mosites at the CDC says, “that linkage to housing needs to remain the most important priority.” While the pandemic might seem to set up a choice for cities between focusing on combating the virus and ending homelessness, the two efforts are linked—and can inform each other. For both, we need good, up-to-date data to understand the scope of the issue, and we need to use it to act swiftly to implement solutions we know can work.