Meeting the challenge of COVID-19 for rural communities of color with better data

The stories we have on COVID-19 to date are primarily urban ones. This is partly a function of data: We just have more of it from cities and metropolitan areas. And we’re seeing that in cities across the United States, people who already face disadvantages are shoulding a disproportionate burden during the pandemic. In the U.S., those are often communities of color. Recently, we spoke with data and public health experts from Kaiser Family Foundation, UChicago Medicine, and more partners about the particular challenges people of color are facing amid COVID-19, and much of what we know right now is based on the urban context.

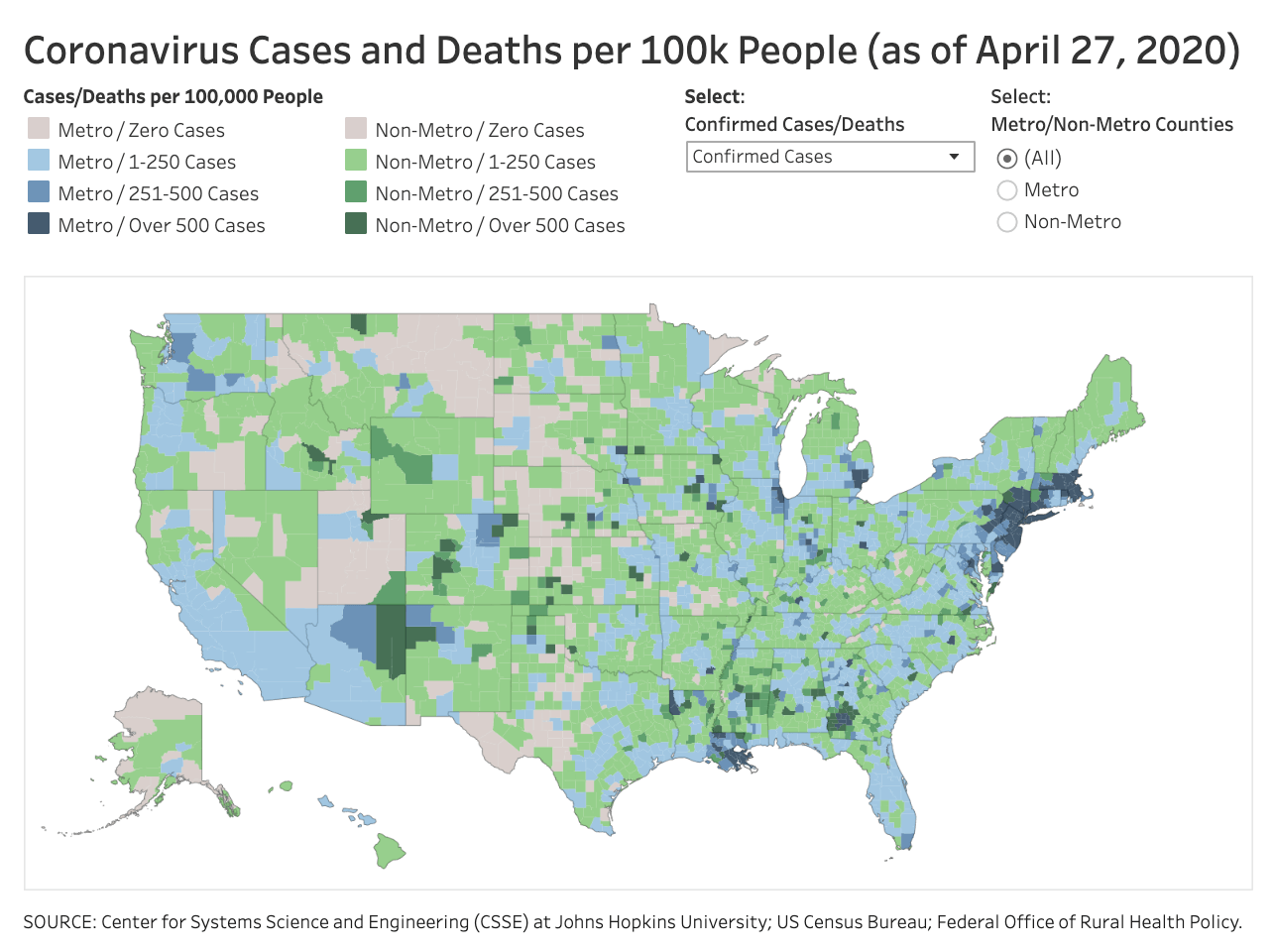

But COVID-19 is affecting rural communities too (for a complete look at where COVID-19 is spreading by geography, see this visualization by our partners at KFF). As the numbers grow, similar disparities along the lines of race and ethnicity are also materializing. As we start to see more data on the impacts across different geographies, we need to understand the particular challenges that rural communities face—and we need to look to the data to inform our understanding of who makes up these communities.

Recently, Amanda Makulec, an advisor on Tableau’s COVID-19 Data Hub initiative, spoke to Bryn Bird MPH, a public health expert with a focus on epidemiology who works in rural health advocacy. “There’s an assumption that rural communities are white and old,” Bird said, but the data tell us otherwise. In recent decades, rural communities have become increasingly diverse: Around one-fifth of the population are people of color. And the challenges facing rural communities are compounded for the people of color who live in them. The fact that rural Americans are more likely to be employed in jobs that are considered essential, combined with the fact that many people in these roles, but particularly people of color, face pre-existing conditions and barriers to healthcare access, is creating a particularly dire situation.

To understand how COVID-19 is impacting rural America, we need thorough knowledge of what the data are telling us about the people in them and the challenges that they face.

This need, though, shows how far we are from achieving it: Rural communities of color are so often overlooked both in demographic analysis and in mainstream media coverage of issues affecting the country. From our partners, we have some sense of what the data can tell us about rural communities of color and how to support them during and after the pandemic. But we need much more data for a truly complete picture.

What we do know: Data show pre-existing health challenges in rural places

“When you look at general health inequities for things other than COVID-19—diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma—rural counties have a much higher premature death rate, and they rate lowest nationally in terms of overall health outcomes,” says Dr. Scott Cook from our partners at UChicago Medicine, whose research focuses on improving the health of minority populations in both rural and urban communities.

“A lot of people assume that lower population density levels become this overriding protective factor for rural communities, and that may play a role, but these other health and wellbeing factors will also play a role,” Cook adds.

Food insecurity is a key challenge in rural communities

We know from our partners at Feeding America, the largest hunger-relief organization in the U.S., that rural communities make up 84% of the most food-insecure areas in the United States, and that food insecurity and lack of access to nutritious food are significant contributors to overall health risks. People of color are also more likely to be food insecure. Food insecurity rates among black people across America were around 21% in 2018—10 points higher than the national average. In tribal communities like the Navajo County in Arizona, food insecurity rates are higher than 26%, and among Latino families, one in six struggle with hunger.

These disparities are due to a combination of persistent poverty, which is pervasive in rural communities of color, and lack of access, due to the prevalence of food deserts. In over 20% of rural counties, according to our partners at PolicyLink, residents have to travel more than 10 miles to reach a grocery store. These populations that were already struggling with food access and the health concerns that go along with it will only face more challenges after COVID-19.

Rural communities face barriers in access to health care

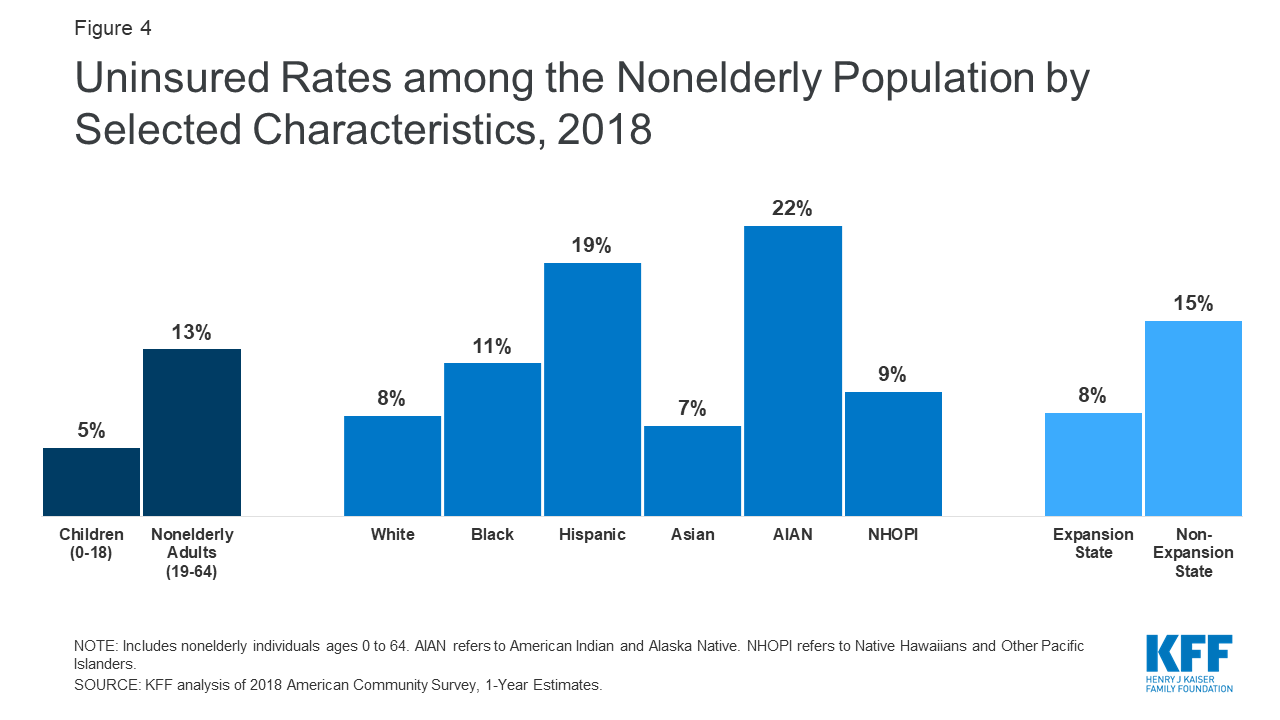

According to our partners at Headwaters Economics, rural hospitals are in a dire situation: In the last 15 years, 172 rural hospitals have closed, and of the ones that remain, at least a third are entirely publicly funded, which means they’re dependent on public spending that’s drying up due to the pandemic. But even if there is a hospital available, rural people of color still face challenges in accessing care: According to KFF, they’re less likely to be insured and able to afford both preventative and emergency care.

Employment trends place rural people of color at risk

Employment data shows that rural Americans are far more likely to work jobs that are considered “essential,” which heightens their risk of exposure to the virus. The Aspen Institute’s Community Strategies Group reports that “while still economically and culturally important, agriculture now employs less than 5 percent of the rural workforce. In fact, across rural America, manufacturing (15 percent), education and health (25 percent), trade transportation, and utilities (20 percent), and leisure and hospitality (11 percent), provide over 70 percent of employment.”

The people who are most vulnerable in these conditions are often immigrants and people of color..As Janet Topolsky, Executive Director for Aspen CSG, writes, family livelihoods in rural communities of color “depend largely on the now “essential” lowest-wage, hard-work jobs such as farm worker, meat packer, cashier, restaurant server, truck driver, home health or child care aide – jobs that today either entail inordinate individual risk or have suffered layoffs.”

A focus on data for solutions

We know there are challenges ahead: The data policymakers have to work with to create solutions for rural communities are incomplete. Even before COVID-19 took hold, CSG, the Urban Institute, and the Housing Assistance Council issued a report calling for better data practices in rural areas to improve our understanding of challenges like persistent poverty, and also what solutions and strategies are most effective in fostering prosperity.

Especially in the context of COVID-19, says Katharine Ferguson, with the Aspen Institute, there needs to be a heightened focus on systemic solutions that actually get to the heart of the underlying inequities—race, place, underlying health and economic status. Building back better includes giving rural regions and tribal nations a fighting chance to thrive in a post-COVID economy. This requires reimagining federal rural policy, and how development investments are designed, allocated and deployed. Ferguson says policymakers should prioritize support that invests in the vision and capacity of local leaders and their solutions, while tracking outcomes closely and with the public-sector providing know-how on what works and why. This would be a big change from current development investments, which support an alphabet-soup of programs and finance lots of projects, but without the backing of a consistent national development strategy or coherent intellectual framework. Overhauling federal rural development policy will require a change in the way policymakers measure and understand outcomes. “The aim of development is improving an overall improvement in quality of life,” she writes in a recent piece for the Aspen Institute. Rather than counting “jobs,” “growth,” and number of services provided, this shift and making sure the solutions in place are meeting needs and creating lasting impact means measuring outcomes. And for that, we need better data collection and analysis—and community buy-in.

Read more recommendations from Aspen CSG here

COVID-19 is underscoring how incomplete our understanding is of America and its challenges—particularly for communities of color. We need a more thorough, responsive, and accurate effort around data collection and use in these communities to truly understand their needs, and get to the heart of why the data we do have are showing such alarming disparities. And then, with that information and in partnership with the communities themselves, policymakers can begin to design solutions that actually get to the root of the issue, and make a lasting impact.