From headlines to headway: Defining data ethics and its impact on data workers

It’s hard to read the news lately without scrambling upon two words in close proximity to each other: data ethics. We’ve seen discussions around privacy, effects of the plethora of data we now have, and the questions around who owns this wealth of knowledge. As people who work in data, we understand the first word fairly well. It’s the second that’s creating the heat.

The amount of data we have multiplies daily. Data has become larger and more granular, with increased depth and density. This enables us as practitioners to move from testing hypotheses on a small and isolated set of data to building detailed profiles of individuals. With this knowledge, we can reshape experiences in the world, which is where we intersect directly with ethics. We are no longer limited by a lack of data, so we are responsible for our own ethical boundaries.

What are ethics?

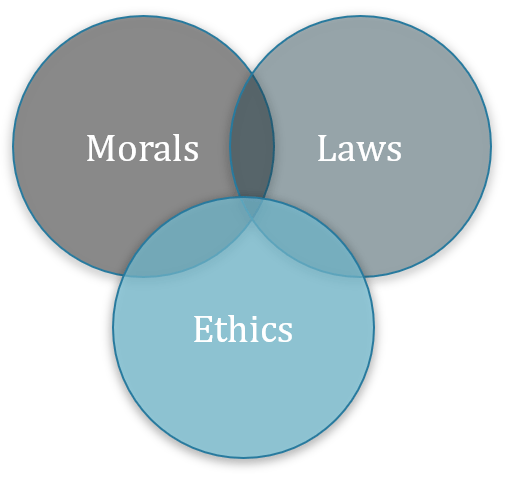

At the intersection between laws and values lives our new hot term: ethics. This word comes to light when things go awry—such as conflicts of interest or ethical violation—but its impact lies within the core of our daily personal and professional decisions.

Ethics come into play on the professional side when we act on behalf of another, either as a trusted advisor or as expert. Professionals are typically expected to focus first on the client, using our knowledge to help others. Doctors do this with patients by monitoring health, diagnosing disease, and providing the best treatment.

To understand ethics, we need to look at values since they closely interrelate. Values are what we, as humans, believe. They’re intensely personal, formed by family, religion, culture, and experience.

We break up values in a few ways:

- Beneficence / non-maleficence: We often recognize this as ‘do no harm’.

- Autonomy: This often gets rephrased as the right to decide or self-determination.

- Privacy: We often apply this to actions or communications occurring ‘in confidence,’ implying that trust is essential and discretion is required.

- Justice: Defined as ‘right and wrong’ or what’s perceived as fair.

- Sanctity of life / physical safety: Literally, the right to exist in an environment that doesn’t harm the person.

- Integrity / honesty: Ensuring that claims are represented fairly and truthfully.

Various industries may group or catalogue values in different ways. These values may overlap or run into contradictions, such as feelings about the death penalty (sanctity of life vs. justice vs. beneficence). As humans, we form our opinions through our values.

Ethics are philosophy

Throughout the history of the world, philosophers have attempted to understand humanity and the world. The latter branch was considered ‘natural philosophy,’ which evolved into what we recognize as science. The former encompasses subjects like law and ethics, in addition to its look into rhetorical skills.

Science and philosophy remain heavily intertwined. Often, a new breakthrough proves we can, with the next question being should we? These innovations not only change something about the world, they in turn shape us, our culture, and the realities we experience.

Data ethics in practice

Both ethics and philosophy provide a process for looking into potential value conflicts. For example, many societies value a level of privacy. As we find more ways to use data for potential benefit, this value runs headfirst into privacy concerns. How much is too much? Who can control this collection? Regulations like GDPR attempt to resolve this, but ethics provide much needed insight.

Numerous ethical review tools exist. As an interpreter, I used Demand-Control Schema extensively for decisions that required an immediate response. In data, we often have more time to make a decision. Using common principles, an ethical review process for anyone involved in data could look like the below diagram:

In more detail, our approach would be:

- Ambiguity: When we encounter a conflict, something may not sit quite right, like a request. It may be unclear what exactly is the issue, so using our categories of values helps us see what’s involved.

- Defining: Having a standard list of values helps us tick through the boxes to identity the issue. Most dilemmas are triggered when two or more values are at odds with each other, such as privacy and autonomy, or justice and beneficence, when we look at data collection, ownership, and data-driven decision-making.

- Analyzing: Once we’ve identified the issues, we’ll have an easier time finding a solution. In this stage, we’ll brainstorm several, even those that may not be practical. Do we provide ways to opt out or highlight weaknesses in data? Do we push for more clarity?

- Reviewing: A list of solutions in hand, we may seek counsel from others to find what’s practical to implement, what hasn’t been considered, and what works best within our organization. We may need someone else to determine the action.

- Deciding: This is where we put our solution into play. We also monitor it and adapt as necessary.

This model helps me consider ethics through the following lenses:

- Data collection: When collecting personal data, do individuals know what I’m collecting, to what level of detail, and what their controls are? Can someone opt out or limit the detail?

- Data governance: Consider who owns the data. If it’s public information, do I make it appropriately accessible while protecting identities enough? Am I transparent enough about the origins of this data and its limitations?

- Data sharing: Consider biases and whether or not facts are being presented clearly. Are filters clearly identifiable and are wise choices avoiding perpetuating bias (such as color choices)? Is this visualization appropriately accessible to the intended audience? Can the audience trace back the data to understand what is and is not shown?

- Data decision-making: Consider how you’re presenting the data. Are the limits of the data understood and does it fit the question? Is the presentation of it deceptive?

The practice of ethics helps practitioners step back and evaluate a situation from an ethical lens. The resulting action could be shaped by corporate values or a professional code of ethics. But above all, data ethics are designed to act as speed bumps in our work, so we understand how to face dilemmas both personally and professionally.

Learn more about recent headlines on data ethics and the impact of these concerns on the modern business model during Bridget's Tableau Conference session, Data ethics | From headlines to headway. Join us in New Orleans and register for TC18 today.

Related Stories

Subscribe to our blog

Get the latest Tableau updates in your inbox.